[Author’s Note: This is Part 1 of a 2-part series on New Hampshire’s Gunstock Mountain.Though usually overlooked when discussing the gnarliest terrain in the east, Gunstock’s contributions to skiing history are monumental, dating all the way back to the primordial age of the sport in America. Small, but plucky, what Gunstock lacks in haute chic, it makes up for in vibe and ergonomics. but that’s a discussion for Part 2. For now, allow me to set the Wayback Machine, Sherman…it’s time for a history lesson.]

The Genesis of Gunstock Mountain

—Special to Slave to the Traffic Light Adventure Magazine, by Jay Flemma—

GILFORD, NH – Score an enormous win for the little guy! Never mind how excellent the skiing is, how easy Gunstock Mountain is to get to, or how rich a winter sports history the region has; everyone should breathe a sign of relief that yet another beloved public-owned and particularly well-run, reasonably-priced ski area has not been swallowed up and homogenized by some 800-pound corporate gorilla. Despite political turmoil in 2022 that actually shuttered the mountain for two heart-stopping weeks, Gunstock Mountain still belongs to the people of Belknap County. And the region, its residents, and all winter sports are better for it.

BELKNAP – THE GENESIS OF GUNSTOCK

They started skiing on Gunstock Mountain perhaps as early as 1918, coincidental with the founding of the Winnipesaukee Ski Club. As NewEnglandSkiHistory.com wrote, “Snow trains carried skiers and spectators up from urban areas to the popular town of Laconia, located just west of the Belknaps Mountain Range. While early ski trails were developed on Gunstock Mountain, Belknap Mountain, and Piper Mountain, skiing on Gunstock in particular was popular, as it was the location of many races, including the 1932 United States Eastern Amateur Ski Association championship.”

It was the Works Progress Administration of the early 1930s, a product of the Great Depression, that provided both the capital and manpower to build Gunstock’s precursor: Belknap Mountain Recreational Area. Again, NewEnglandSkiHistory is instructive:

“The initial plans for the $300,000 Belknap Mountains Recreation Area included the 60 meter ski jump, a slalom course, and two new ski trails. [Author’s Note: Yes, Gunstock started as a ski jumping venue…] The multi-sport facility plan was so large that it was even suggested as a location for the 1940 Winter Olympics. The Belknap Mountains Recreation Area was officially opened on February 28, 1937 when it hosted the United States Eastern Amateur Ski Association ski jumping event….Work on the development continued throughout 1937, with Hussey Manufacturing Company leading the way. A novice slope was cleared on Cobble Mountain while the main work effort was taking place on Mt. Rowe: the installation of the East’s first chairlift.”

The single chairlift, climbing from Gunstock’s present base area to the top of satellite peak Mt. Rowe, began spinning late in the winter of 1937-38. The “controversial installation” was described by the Lewiston Evening Journal as making the area, “a rendezvous for lazy skiers.” Shrugging off the shade, “lazy” skiers flocked to the Belknaps, eventually helping cement chairlifts as the primary form of uphill travel for alpine skiers. As such, Robert Sullivan of Boston Magazine provided a much more glowing assessment than the writers in Lewiston: “Gunstock and neighboring mountains Belknap and Rowe—the latter of which was home to New Hampshire’s very first chairlift—can and should be regarded as venerated ski mountain trailblazers in America.” He was a thousand times right.

Thriving and prospering followed for three full decades. In the winter of 1940-41 a $100,000 base lodge and operations station opened, constructed of local timber and stone cut from Cobble Mountain. And as the post-war era progressed the mountain expanded, much of the growth occurring under the stewardship of as unlikely a character as we have ever met in skiing history: a motorcycle enthusiast named Frank “Fritzie” Baer.

That’s one of the wondrous attributes of our sport. It’s a big tent.

Born in Massachusetts, Baer left school in eighth grade, working instead at a mill, but later shilling for a motorcycle company while moonlighting as founder and operator of a motorcycle club called “Fritzie’s Roamers.”

Waste of time? Just a hobby? Guess again. Deftly using his contacts from both the club and his employers, his first public motorcycle rally drew a whopping 10,000 bikers, an astonishing feat in 1938. The event blossomed into an annual tradition, the Laconia Bike Week, and cemented his reputation as a talented, highly successful organizer and inspiring leader. Deeply impressed by his passion and results, in 1950 county brass chose Baer as the new manager of the ski area, even though he wasn’t a skier. Nevertheless, his ten-year tenure saw growth and modernization. Chairlifts were installed, a novice area was constructed, new trails were cut, and – most importantly – the mountain shattered financial records year after year.

The 1940s and ‘50s also saw the rise of perhaps the three brightest stars of the Belknap/Gunstock galaxy – Hall of Fame ski jumper Torger Tokle and Olympic skiing immortals Penny Pitou, and Egon Zimmerman.

Torger Tokle started soaring from 40-meter jumps at age six. Born in 1919 to a poor Norwegian family, Torkle’s father made his son’s first skis out of barrel staves. A prodigy from the start, the short (5’6”) but stocky Torger’s frame didn’t resemble the typical long, lanky bodies of the great jumpers of the age – Reider Anderson or Alf Engen – but Tokle dominated the sport from the moment he arrived in America on January 29, 1939. Indeed, the first thing the 19-year-old Tokle did – a mere 18 hours after he got off the boat – was win the ski jumping tournament and set the hill record at Bear Mountain Park in upstate New York.

To give you some perspective, the first thing my 19-year-old grandfather Gideon did when he got off the boat was run out of money in upstate New York.

It’s nigh impossible to overstate how dominant Tokle became; in his short, but sensational six-year career, he won nearly every ski jumping contest he entered – a whopping 42 out of 48 events, an astonishing 87.5% winning percentage. During that run, he set 24 mountain records. His biography in the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame highlights just a few of his remarkable achievements:

— Although he was designated a class “B” jumper for 1939 due to a quirk in the National Ski Association rules, he soundly thrashed all the class “A” riders, winning seven of eight tournaments, including tying Reider Anderson for first place at the event in Laconia, forever enduring him to the region as one of their own;

— In 1940, he won every ski jumping tournament except one, the U.S. National Championship. Alf Engen, regarded by many at the GOAT of ski jumping, edged him out, though Engen never again defeated Tokle in competition;

— In 1941, he captured the U.S. national title that evaded him the year before; and

— He was beloved by everyone: competitors, media, and fans. The Hall of Fame remembers him glowingly as, “A top-flight sportsman to every end, Torger Tokle was the kind of person everyone was proud to call a friend.”

Take a moment to consider those well-chosen words more closely for a moment: “A top-flight sportsman to every end.” That truly is, perhaps, the greatest compliment any professional athlete could aspire to achieve.

Entering the army in October of 1942, serving first in the infantry and then later in the fabled 10th Mountain Division, Tokle was killed by the Germans on March 3, 1945 during the Battle of Riva Ridge’s Operation Encore. His foxhole partner’s duty was to carry around a backpack full of high explosives, and when a German artillery shell hit his buddy, the resulting explosion killed Tokle as well. His platoon mates and friends called his death “the worst day of the war.” Recalled by many of that era as “the Babe Ruth of Ski Jumping,” Tokle was posthumously elected to the U.S. National Ski Hall of Fame in 1959.

Although the tiny Gilford Outing Club Penny Pitou grew up in produced fellow Olympic athletes Dick Taylor (cross country in 1964) and Marty Hall, Jr. (a cross country coach across five Olympics for the U.S. and Canada), Penny is undoubtedly the most accomplished alpine skier hailing from the local area. A mere senior in high school – when most 17-year-olds are worried about dates, pimples, and homework – this bubbly and effervescent “Princess of Europe” (as Life Magazine put it) raced slalom, giant slalom, and downhill at the 1956 Olympics in Cortina, Italy.

Then it was time to walk in high school graduation.

Pitou matriculated to Middlebury College in Vermont in 1957, now a powerhouse in alpine and nordic skiing, but back then a program only beginning to emerge. (The men’s team had just finished third in the 1956 NCAA National Championships at Winter Park.)

“I loved skiing and languages – I’m fluent in German and more than proficient in French – and I chose Middlebury thinking that they had a women’s team, but there was no women’s program at the time,” she stated.

Balancing school and skiing, Pitou had her sights fixed firmly on the 1958 World Championships at Bad Gasgein, Austria. While she tirelessly studied and trained, Gilford locals and myriad supporters collected $450 to pay for Penny’s airfare to California for the last tryout race for the team. She repaid their largesse by narrowly seizing the sixth and final spot on the team. She was going to Austria.

“I think the woman that got seventh still hates me,” Penny quipped laconically.

As the months passed and Bad Gasgein drew closer, Penny and her teammates went to train in Europe. Anxious to dial in the specs for her skis and see the latest technological advances, Penny took the opportunity to visit the Kastle factory. It was there that, completely by chance, she saw her future husband, Egon Zimmerman.

“I’m standing there, and in walks this man – very tall, very dark, very handsome,” she recalled fondly. So she asked a worker about him. The conversation was to the point, according to Penny:

Penny: Who is he?!

Worker: That’s Egon Zimmerman.

Penny: Does he have a girlfriend?

Worker: No.

Penny: Is he a good skier?

Worker: Yes, one of the best in the world.

Penny: Does he speak English?

Worker: No

Penny: I want to meet him.

Zimmerman, a native of Innsbruck, Austria, was, – like Penny – a young, but fiercely talented racing prodigy. Zimmerman had been named to the Austrian junior team in 1955 when he was just 16 and – also like Penny – came from a humble background. It was a good match, and Penny knew it. So, she planned her pursuit with masterful precision and cunning charm. She knew she’d see Zimmerman three weeks later at the Hahnenkamm, so she asked her coach to teach her how to say something in German, so she could start a conversation with the Austrian

“I introduced myself by saying ‘You skied very well today” in German. It’s a good thing he did. It was the only German I knew.”

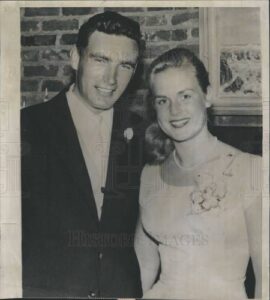

Egon and Penny’s love that grew strong despite being separated by an ocean, and both athletes’ careers soared as their relationship blossomed, their wholesome, humble backgrounds and Hollywood good looks making them 1950s skiing’s proper rejoinder to Travis Kelce and Taylor Swift. (Or is it Mikaela Shiffrin and Aleksander Kilde? I never can remember…)

Pitou won two Olympic silver medals in 1960 on home soil at Squaw Valley, earning personal congratulations from then Vice President Richard Nixon after her first medal…if you can call it “congratulations,” that is.

“He was a big guy, and he came in with a big group,” Pitou stated tersely. “From across the room he looks in my direction, and I think to myself, ‘Oh my God. He’s coming over to me. And I distinctly remember there were three hairs on the top of his nose blowing in the breeze, and he said ‘Penny I’m here to tell you how sorry I am that you lost today.’ I said, ‘But I won a silver medal,’ and he replied, ‘You have two more chances to win for America.’ And turned around and walked away.” She won her second silver medal two days later. Thankfully, Nixon didn’t come back to “congratulate” her again. Still, the rest of America knew what escaped Tricky Dick (fitting nickname in light of this story…). Penny was a national hero.

Penny didn’t just go out like a champion: she went out like a legend. As so few athletes of any age do, she retired on top, right after the Olympics ended.

“I’m getting old,” the 20-year-old Pitou said in the afterglow of her success at Squaw. “In truth, I also nearly fell on my face during the downhill and thought to myself, if you fall here, you’ll have to do this for another four years.”

She returned home to Gilford, the couple married in February 1961, and Penny was inducted into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame later that spring. Revered as hometown heroes in the region, Penny and Egon ran the ski school at Gunstock for many years. In 2009 Gunstock dedicated the Penny Pitou Silver Medal Quad, a new Doppelmayr CTEC fixed grip quad serving a significantly expanded beginner area. Still prim as a cameo, spry as a teenager, and ever the perpetual motion machine, Penny now spends her free time doting on her grandchildren. Her granddaughter, Zoe Zimmerman competes with the U.S. Alpine C Team, and both of her grandsons – Dylan and Zane – are fabulous skiers as well.

As an aside, Gunstock sure has the market cornered for alliteration: Torger Tokle, Penny Pitou, Zoe Zimmerman…quick! Someone call Jeremy Jones and Carolyn Kunkel, and invite them to the party!

“When they were eight and 10, Zoe and Zane and I skied KT22 together, the course where I won an Olympic silver on nearly the 50th anniversary of my run,” she beamed proudly. “And Zane and I skied Val Gardena just this past week.” And there’s yet another reason to visit Gunstock. You can shred with a legend, if you can keep up that is.

To Be Continued…