After sending a twisting, long-distance, double breaking putt towards the cup, the PGA of America left itself with just a tap-in, so allow me to do the honors: the PGA Championship is not “Glory’s Last Shot,” but “Glory’s Best Shot.” Make that small change and watch the slogan catch fire like a hit song by U2.

Nobody gives a professional golfer a better chance to win a major championship than the PGA of America. You don’t have the cloak and dagger fear of the U.S. Open. You don’t have the weather squalls and quirky bounces of the Open Championship. And you don’t have the mystique and aura of the Masters intimidating half the field into the lower hinterlands of the leaderboard before they tee off. At the PGA Championship, by virtue of the familiar parkland courses and scoring-friendly set-up, what you see is what you get, so everyone is invited to the party – may the best player win.

“The PGA of America may have thought that the tournament had an identity crisis, so they went with former U.S. Open venues and a slogan to jazz things up a bit,” explains golf expert and life-long fan John Van Zoost. “But with their long, storied history, warm, welcoming atmosphere, and dedication to the game, they have just as venerable a place in golf history as any other major. They don’t need to do anything except be themselves.”

Van Zoost raises an interesting point. A few venue experiments in the ’70s and ’80s went awry, (PGA National and Crooked Stick for example). But then the tournament started to visit excellent venues like Baltusrol and Oakland Hills and the “too easy” label proved a myth. Indeed, many think the Oakland Hills was set up too hard, and that the torrential rains saved the tournament as great players like Harrington and Garcia could shoot epic rounds and stage a memorable battle. Harrington’s 66-66 finish is just as remarkable as Hogan’s closing 67 in 1951 and Gene Littler’s final round 68 in 1961, which allowed each to conquer “The Monster” and claim the U.S. Open title.

But rather than give in to feelings of inferiority, the PGA should and now does embrace its true identity – the chance for everyone, anyone to attain golf immortality. Some, such as Nicklaus and Tiger, add to their legend by collecting Wanamaker trophies in droves. Others, such as Wayne Grady, Rich Beem, and Shaun Micheel quietly savor their week in history for the rest of their lives, and hey, who are we to belittle their relative obscurity. They survived the crucible of a major – lift them on up.

That is the true greatness of the PGA Championship – its egalitarian nature. Few people back into it, (unless, of course, a leader drives 70 yards right on the 72nd hole and then can’t identify a bunker after a week of play. Dustin, that was your fault, but I digress…). You have to come out and grab the PGA Championship with both hands, then hold on in the scrum. Atlanta Athletic Club, site of the lowest aggregate score ever posted in 151 years of major championship history in 2001, will do just that.

Golf has been a part of Atlanta Athletic Club since 1904, when the club was located on East Lake and featured a course on that property. The club sold that land, (which subsequently became East Lake Club, home of the Tour Championship), and opened on its present site in what was then an unnamed, unincorporated part of Duluth in 1967. In 2006, the region took the name of “Johns Creek,” which will explain all the print writers’ by-lines come tournament week.

Rees Jones has done a renovation of the Highlands course, nine holes of which were designed by his father, Robert Trent Jones, Sr., and nine holes of which were designed by Joe Finger, another designer best known for penal architecture. The course is another in the seemingly endless line of clubs that, during the “harder is better” period of architecture asked for a U.S. Open venue and, mostly due to both Bob Joneses’ standing in the game – not just RTJ, Sr., but golfer Bobby Jones as well – got it. It hosted its only U.S. Open in 1976.

Georgia native Jerry Pate gave that tournament an indelible, indeed iconic moment with a 194-yard 5-iron approach to the 18th green out of heavy rough over water to two feet for a kick-in birdie, a two-shot victory, and his only major championship. The astonishing thing was, he did it as a rookie.

“You’re not supposed to win a dignified, ivy-covered, crusty old championship like the U.S. Open unless you’re well versed in the history of Francis Ouimet’s knockers,” wrote one irreverent wag. Pate was more laconic…

“How ’bout that, sports fans?” he drawled humbly.

At the 2001 PGA Championship, David Toms wrote his name into the history books by doing just the opposite. Locked in a grueling, 18-hole, mano-a-mano duel with Phil Mickelson – who at that time was not only seeking his first major, but striving to get the evil moniker of “Best Player Never to Win a Major” off his back – Toms, like Pate, drove in heavy rough on 18 while clinging to a one stroke lead.

Never known for length, Toms had to lay up to 100 yards, a comfortable length for a full wedge. He played to 12 feet and, like Payne Stewart two years earlier at the U.S. Open at Pinehurst, rolled in the par putt to deny Mickelson, and claim his only major to date.

Poor Mickelson! His 266 aggregate score was good enough to win every single stroke play major championship in history except that one. (Remember: for several decades, the PGA Championship was a match play event.) The Golf Gods can be cruel at times.

This year the Highlands Course will become only the fifth club to host three or more PGA Championships. The list is a “Who’s Who” of historic courses: Southern Hills, Oakmont, Firestone, and Oakland Hills, nice company. For those of you scoring at home, the other PGA Championship it hosted was won by Larry Nelson in 1981, like Pate, another Georgia boy who gave all the hometown fans a thrill with sparkling play and a folksy, humble demeanor.

The club is steeped in not only golf history, but athletics in general. The legendary amateur Bobby Jones was not only a member, but the club president. In 1908, the club hired Georgia Tech football coach John Heisman as its athletic director. The club also hosted the 1990 Women’s Open, won by Betsy King, and will host the 2014 U.S. Amateur.

THE HIGHLANDS COURSE

Although the bones of the course are a Jones/Finger mix, the Highlands Course is reminiscent of many of Trent Jones Sr.’s other major championship venues like Hazeltine and Medinah: tree-lined, bunkers on either or both sides of the fairway, gargantuan length, ubiquitous ponds with steep slopes and shaved banks making the hazard far larger than the water-line, and large but somewhat flat greens that need to be reached with high lofted shots because they are surrounded by trouble. Typical of both Jones and Finger, it’s double target golf.

In other words, it’s nothing they haven’t seen before, so players will feel comfortable.

Now there has been much discussion of new turfgrasses being tested for the first time here at the Highlands Course: new strains of grasses that are heat resistant and should open the door to more southern venues hosting major championships. While these new grasses may play more “fast and firm” than the old grasses, Atlanta is still hot and muggy during summers and the soil is still thick clay, so conditions may still be somewhat soft. The climate there is much like the climate at Congressional, so this author believes scores will be low as a result, possibly double-digits under par, especially on somewhat flattish greens, (even at the estimated stimp figure of 13.5). With that in mind, let’s take a look at a few interesting holes.

Hole 2 – Par-4, 512 yards – Converted from a par-5 for members, its main defenses are length, a narrow fairway, and a diagonally placed green the axis of which is not pointed back down the fairway. “Draw off the tee, fade into the green” is the textbook play, but pros with modern equipment routinely make a mockery of such strategies.

Hole 4 – Par-3, 219 yards – I really like this hole. With water all along the left side, the green cuts diagonally from back left to front right. Golfers playing away from the water will steer themselves right towards a bunker. If they end up in the sand, they play the next shot right back towards the water they tried to avoid in the first place. (As an aside, this is actually a staple par-3 template out of Pete Dye’s playbook, so look for it next time you’re on a Dye course. Think, for example, 12 at Bulle Rock.) Playing out of the sand back toward a pin tucked near the water is a white-knuckle proposition.

Hole 5 – Par-5, 567 yards – Hit the fairway off the tee and it’s a cast-iron birdie hole. A cross-bunker was added at the 100-yard mark, but that shouldn’t stop the hole from reprising its role as the easiest hole on the course, like in 2001.

Hole 6 – Par-4, 426/295 – In a bit of “monkey-see, monkey-do” apery taken from Mike Davis’s U.S. Open playbook, rumor has it the tee on this hole may be moved to the 295 mark to give the pros a chance to go for the green, but who will be lunatic enough to risk trying to drive through a 20-yard wide fairway where the entire thing slopes towards the water? Only the longest hitters stand a chance to reach this green surrounded by bunkers and a pond, and they’re more likely to blast it over the water and the green into a bunker for a chance at an up-and-down birdie. Still, why risk a bogey or worse it when you’re going to have a wedge in your hand for your second if you lay back? Too much risk, not enough reward.

Hole 11 – Par-4, 457 yards – If a class were offered in “Golf Archi-torture 101 it would feature this hole – a sharp dog-leg left with a fairway bisected by a cut of rough with a wedge shot approach to a long narrow green with water all along the right of the green and behind it as well. Two large bunkers guard the left side of the green, so the entire putting surface is, again, completely surrounded by hazards. If, as the yardage book says, “wedges could spin back into the water too,” you need to blow up the hole and start again.

Hole 12 – Par-5, 555 yards – Take the same exact hole as 11, just make it a par-5. If the tee shot fails to make the corner of the dog-leg, it leaves a dicey lay-up because the landing area gets narrower the closer you get to the green. Golf Archi-torture 102.

Hole 15 – Par-3 258 yards – Though the hole has been a watery grave for contenders for 35 years, two different major champions used this hole as a springboard to victory. David Toms made a hole-in-one on this hole from 242 yards in the third round in 2001. Jerry Pate put a 2-iron to eight feet and made birdie in the final round in 1976. In 2001, this par-3 played to a stroke average of 3.342, second hardest hole on the course and one of the 50 hardest holes the PGA Tour pros played that year. The most difficult during the event was 18, a par-4 which played to an average of 4.398.

Hole 18 – Par-4, 505 yards – Speak of the devil. Everyone in golf knows this hole. The edge of the lake begins at the knee of this 45-degree dog-leg left and extends all the way to the green, cutting in front of it. Despite its penal architecture, it’s a dramatic finisher.

With modern equipment, the Highland Course’s length will not faze the players. The new strain of rough, “Tifton 10” will be mowed to a friendly 2-1/2 inches, and will hold balls up much better than the old Bermuda, which not only made the balls sink, but also tended to cling to the club head and hosel. In short, this should be the easiest set-up for a PGA Championship since…wait for it…the last time we were at Atlanta Athletic Club in 2001.

As a result, there should be remarkably little hand-wringing and whining about the golf course. Everyone should feel comfortable here, but American players in particular will be eager as a gundog who just heard his owner take the firing piece down from over the mantle. Even journeyman pros may catch fire and find themselves on the leaderboard come Sunday.

This will be an excellent opportunity for Americans to end their major-less streak at six, although a few of the usual suspects among the foreign players should play well here as well, including Y.E. Yang, Jason Day, (who always seems to be in the mix at the big tournaments), Lee Westwood, and Rory McIlroy.

So many Americans will have a chance that it’s nigh impossible to sift through the pile and pick some favorites, but keep a special out for young American star Webb Simpson, the former Wake Forest phenom who has quietly been having a superb year. Maybe it won’t be this week, but he’s on the cusp of winning a major. He’s a breakout star in the making, and a super-nice young man as well, a clean cut, forthright young man the public can admire. Zach Johnson tends to play well in Georgia, David Toms is having a good year, and Phil Mickelson shows signs of returning to form, though if his driver abandons him, the trees could be his undoing. Finally, Dustin Johnson could catch fire and bring the course to his knees. How interesting would a DJ vs. Rory battle be?

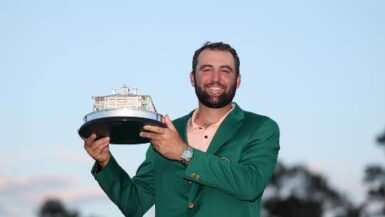

So in less than a week, like the shuttering of a great lamp, darkness will fall on another season of golf’s major championships. It’s been wondrous to behold so far: a sparkling Masters with ten players in contention late into the back nine, an historic, record-setting performance by a young superstar at the U.S. Open, and a heart-warming resurgence of one of the game’s most popular and esteemed gentlemen at the Open Championship. Expect nothing less at this year’s PGA Championship. When all 156 players all have a chance at contending, it’s the fans of our great game that win in the end.