SOUTHAMPTON, NY – I want to thank the great Dan Jenkins for today’s writing prompt. He published some of his favorite (and not so favorite Opens) and reminded me that it’s time for my annual U.S. Open history lesson for y’all. So here we go; class is in session. Take good notes. You never know when you’ll be quizzed.

GREAT STORIES YOU NEVER HEAR ABOUT, BUT NEED TO KNOW

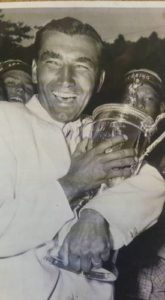

1. 1946 – Lloyd Mangrum at Canterbury in Cleveland. WWII interrupted a great many touring professionals lives, but while Hogan, Snead and others got cushy military base golf pro jobs, Lloyd Mangrum saw the most serious action of the war. He could have taken a head pro position at an army base in Maryland, but he turned it down. Instead, serving under Patton, Lloyd Mangrum, or as I like to call him Lloyd Mangled, was wounded landing at Normandy, wounded again at the Battle of the Bulge, and then later had a jeep overturn on him. He won two Purple Hearts. After the War, he returned stateside and won the first post-war Open, in 1946. (There were no U.S. Opens contested between 1942 and 1945.)

Dan Jenkins, put your hand down! We know about the 1942 Hale America Open!

Anyway, Mangrum bested both Byron Nelson and Vic Ghezzi in an 18-hole playoff at Canterbury. It was a momentous victory; Nelson was the reigning PGA Champion and had recently run off his record 11 straight PGA Tour wins. Mangrum, though, had a sterling career as well. He won two Vardon Trophies and finished top-10 in the Masters ten consecutive years at one point in his career.

Incidentally, neither the Germans, nor Nelson and Ghezzi should have felt at all bad about not being able to finish Mangrum off. The Devil himself had trouble: Lloyd survived 11 heart attacks before the 12th finally killed him at age 59.

2. 1954 – Ed Furgol at Baltusrol (Lower, and at one point, Upper). While he wasn’t as chewed up as Lloyd Mangled, Ed Furgol was equally famous for his injury: a withered left arm, 10 inches shorter than his right due to a spectacular compound fracture he sustained in a childhood fall off a jungle jim. It was improperly set, resulting in a grievous-looking deformity, but Furgol worked around it brilliantly. He first excelled at boxing of all things – back then kids picked on cripples, and Furgol vowed not to become prey for bullies – then he took up golf, and had a stratospheric amateur career, winning the illustrious North and South, before suddenly losing his form just six months into his professional career.

Furgol won the ’54 Open as a club pro from St. Louis. His sponsors gave other golfers courtesy cars, while he paid out of pocket the equivalent of $100 a day to take a cab to and from the course. He was assigned a random guy off the street as a caddie, someone who knew zero about golf and couldn’t even remember to keep Furgol’s clubs clean. His win was a bolt from the blue in every way imaginable.

A dead ringer for actor Bela Lugosi of Dracula fame, Furgol played defensive golf all three days – “I was shooting for greens, not pins,” he explained, and it worked. He hung around the leader board with his steady, careful golf, and actually led the tournament after the Saturday morning round. He held on for a 1-stroke victory by playing his second shot up the fairway of the adjacent Upper Course, then bump and running a shot through the trees to the edge of the green for an easy two-putt and the win.

Originally from the Utica, New York area, Furgol triumphantly returned to Utica for a parade up Genesee Street and a 9-hole exhibition at Valley View Golf Course, where his brother Hank was the head professional. Furgol got out of the limo, and promptly drove the first green – 320 yards uphill, with persimmon – en route to a 5-under 31.

3. 1977 Hubert Green at Southern Hills G.C., Tulsa, IL. While trying to win the Open, Hubert Green had a lot more to worry about than the streams, bunkers, and fearsome green contours of Southern Hills. He played the last four holes under a death threat.

Earlier in the day, a woman had called the police and said four men were headed to the golf course to shoot Green as he played the 15th hole. As Green walked off the 14th green with a 1-stroke lead, he was suddenly aware that uniformed officers and officials were approaching him, looking more grim than usual. They explained that they received the threat and gave him three options: stop play altogether, send all the fans home and then finish the round, or just keep playing while surrounded by a phalanx of armed officers.

Green famously remarked something about, “It sounds like an angry ex-girlfriend. I’ll keep playing.”

Still, he made sure to stay as far away from his caddie as possible until he finished the round. Green hooked his drive on 15 into a tree, which likely saved it from going out of bounds. He scraped a par – literally the par of his life – and then birdied 16, giving him enough cushion to survive a closing bogey at 18.

TOP 10 PRE-1960 U.S. OPEN VENUES THAT ARE NO LONGER IN THE ROTATION

This list is like giving a starving man a menu; you’ll remember playing any of these courses fro the rest of your life. They are all superlative, and the list is striated more by my personal taste than any semblance of one being that much better than any other.

1. Garden City Golf Club, NY (1902)

2. Chicago Golf Club, IL (1897, 1900, 1911)

3. Philly Cricket Club, PA (1906, 1910)

4. Myopia Hunt Club, MA (1898, 1901, 1905, 1908)

5. Southern Hills C.C., OK (1958)

6. Riviera C.C., CA (1948)

7. Canterbury G.C., OH (1940, 1946)

8. Colonial C.C., TX (1941)

9. Baltimore C.C., MD (1899)

10. St. Louis C.C., MO (1947)

Note: The Roland Park Course of Baltimore C.C. which hosted the Open no longer exists. Instead, golf pilgrims visit the club to play the A.W. Tillinghast designed East Course, beautifully restored to to its Golden Age grandeur. Similarly, although the 9-hole St. Martin’s Course was the Open venue at Philly Cricket Club in 1906 and 1910, the Wissahickon Course may host a PGA or an Open some time n the future, the restoration/renovation is that spectacular. That’s now the flagship of the 45-hole club, although you can still play St. Martin’s as it meanders serenely though its charming neighborhood.

Canterbury and Colonial are not just great clubs and courses, they are museums of golf history, and you walk the halls in almost church like reverence of the history that graces the walls. With the right kind of eyes, you’ll think you’ve been transported back to the formative years of the game. It is absolutely imperative for any golf fan to make the pilgrimage to these shrines, just as priests and penitents walk the Circus Maximus in Rome – you, like they, are on Holy Ground.

As an aside, we’ll be playing and reporting back from Myopia Hunt Club later this summer. I brought up Myopia’s name when my Boston wingman, Mike Mosely, said he was up for a low key round, and his tirade has entered into legend…

“Let me tell you what low key is NOT, Jay,” he raged. “Low key is NOT a fox hunt after the round. Low key is NOT playing with Robert Andrew Buffington the Third, President of the Club, member of the Royal Society, and direct descendant of Sir Joseph Blaine. Low key is NOT 20 foot deep bunkers all day and four walks of shame while shooting a number that looks like the temperature in Death Valley! Can’t we just go to Granite Links? The bar scene there is hot.”

While he’s right about the bar scene at Granite Links – hottest pickup scene in public golf – I put my foot down, and we play Myopia this summer.

BEST VENUES EXPECTED TO RETURN TO THE ROTATION

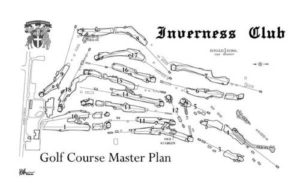

1. Inverness Club – Toledo, OH – Inverness is all the talk amongst the cognoscenti as it is one of two frontrunners expected to return triumphantly to the U.S. Open rotation. Dating all the way back to 1903, club hosted the Open three previous times. 1931 is infamous for beastly heat (it was 105 the first day) and the 72-hole playoff between eventual winner Billy Burke and runner-up George Von Elm. Not only were they bruised for four rounds to the tune of 8-over par, they had to endure another four rounds to determine a winner.

“The famous double Open!” quipped preeminent golf historian Bob Crosby, chair of the USGA Architecture Archives Committee. That was the end of 36-hole playoffs.

Interestingly, Burke smoked cigars constantly, because he claimed it helped him see which way the wind was blowing. He went through 32 cigars in 144 holes. It is not reported how many breath mints he needed to kiss his wife afterwards.

1957 was equally brutal heat as well, above 90 every day. The biggest news was Ben Hogan withdrew, unable to swing the golf club. Dick Meyer, who apprenticed with Claude Harmon at Winged Foot, defeated defending champion Dr. Cary Middlecoff in a playoff on his way to Player of the Year honors. Playing in his first U.S. Open, a 17-year old Jack Nicklaus shot 80-80 and missed the cut.

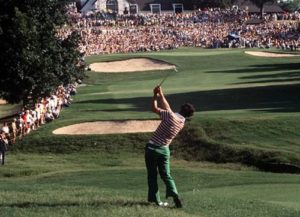

1979 was the year that saw Inverness’ fortunes decline. A George Fazio redesign of several holes was universally panned as completely incongruous with Donald Ross’s brilliant design, as well as dreadfully dull. A tree-planting campaign had erased much of the course’s strategy and character, turning it into a bowling alley. And, of course, the USGA planted the Hinkle Tree in the wrong place during the night after round 1, allowing Lon Hinkle to make them look silly twice in two days. Inverness, it seemed, was no longer U.S. Open-worthy. Happily, a restoration project spear-headed by Andrew Green is enjoying unanimous acclaim.

“It’s the best renovation job I’ve ever seen,” praised well-decorated amateur and mid-amateur champion Alan Fadel. “They brought the course back by replacing the George Fazio holes with holes that have the same type of character and strategies that Ross had designed. Andrew Green has truly established himself as one of this country’s best restoration architects. You look at some of these holes, and you don’t know if you’re in Toledo or Dornoch.”

2. Oakland Hills C.C., MI – Another ancient and venerable Midwestern Donald Ross club, no course has as much of a major tournament pedigree except Oakmont. The routing cunningly twists and turns serpentinely, a Gordian knot with the two nines intricately intertwined. The fairways heave like a tempest tossed sea, and the green complexes rival those of Winged Foot, Oakmont, and Shinnecock Hills.

Unlike many former U.S. Open courses that no longer are capable of hosting majors, Oakland Hills’s orbit intersected with that of the PGA of America, and they held two Ryder Cups and a PGA Championship in this century. Padraig Harrington played 3 holes on Sunday in 2008 to post a final 36-hole tally of 66-66 to edge Sergio Garcia and Ben Curtis.

Although officials will never admit to it, the USGA and PGA of America have essentially done a trade – Bethpage Black, site of the 2002 and 2009 U.S. Opens became a PGA of America venue and will host the 2019 PGA Championship (the first in May) and the 2024 Ryder Cup, while Oakland Hills already hosted the 2016 U.S. Amateur and is being renovated as we go to press in a final push for a U.S. Open in 2028 or 2029. After all, the USGA still needs a Midwestern venue in the location, and Oakland Hills is perfect. Like Oakmont, it could host an Open with even mere weeks to spare, the course is that challenging.

MOST DRAMATIC VICTORIES (POST-1960)

1. 1982 – Tom Watson at Pebble Beach. The sight of Jack Nicklaus charging up the leader board on a Sunday at a major was enough to freeze the heart of any golfer with terror, but Tom Watson reprised his two great 1977 battles with a Sunday donnybrook for the ages. After bogeying the 16th by hitting into Sandy Tatum’s new fairway bunker – “We put it in to catch guys just like that…” Tatum said as Watson had to play out sideways – Watson, now tied with Nicklaus for the lead, hit his tee shot on 17 into ankle deep in rough over the green.

“Bogey,” thought Nicklaus. “I win.”

Then Watson reached the ball, saw he could get his wedge on it and told Bruce Edwards, his caddie, “I’m going top make it.”

He did just that. Then he birdied 18 to put an exclamation point on his only U.S. Open win.

2. 2000 – Tiger Woods at Pebble Beach. Tiger didn’t just win his forst U.S. Open, he throttled it. He pounded it and the rest of the field into tiny, unrecognizable bits. After he won by 15 shots, Ernie Els groused, “If he wins by 15 at St. Andrews, there ought to be an inquiry.”

3. 1980 – Jack at Baltusrol (Lower). Jack opened with a 63, but could never shake plucky Isao Aoki of Japan, a puzzling stranger with a quirky putting style who refused to go away until the end. Jack had to play the closing par-5s birdie-birdie to finally shake him and win by two strokes, posting a then U.S. Open scoring record to do so.