Just under eight miles as the crow flies from Bellerive Country Club, site of this week’s 100th PGA Championship, while the golf world celebrates the PGA of America’s centennial anniversary, a far more grave, but just as riveting drama is unfolding.

St. Louis was where much of the uranium used in the first atomic bombs was enriched. Although those bombs helped bring about an end to World War II, that uranium has also left a terrible legacy since then: the 47,000 tons of Manhattan Project atomic waste were moved around several residential neighborhoods and various downtown locations. As CBS News reported Tuesday of tournament week, tens of thousands of barrels, many left open to the elements, contaminated the ground, air, and water of several North St. Louis County neighborhoods throughout the intervening decades.

But now the illegally dumped waste is threatened to be breached by an underground landfill fire, (called a “smoldering sub-surface event”). If the fire ignites the waste, the windblown radioactive particulates in the smoke plume could attach to potentially anyone and anything within a several mile radius in this major metropolitan center.

It’s only just now that the nation – indeed, the world – have heard about this. If not for a frightful stench emanating from the landfill, a tireless homeowner’s group called “Just Moms STL,” and the watchful eye of a seasoned, award-winning documentary filmmaker named Rebecca Cammisa, both the leaking atomic waste and the fire might have stayed below the public’s radar until an immediate emergency occurred. But even before the fire, inordinate numbers of St. Louis residents in the numerous affected areas have died of the same cancers human beings can contract from exposure to ionized radiation, the long, slow, insidious creep the waste’s radioactivity has allegedly caused during these long years.

Although public meetings have been held for six years, little to nothing of substance was done until recently to stop the fire’s slow advance. And much still needs to be accomplished – and rather quickly – to halt the fire, clean up the waste, and compensate the homeowners whose lives have already been decimated by cancers caused by exposure to ionized radiation from the leaking atomic toxins. Happily, after years of delays, it appears help finally may be on the way.

BACKGROUND – THE MANHATTAN PROJECT AND ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI

In 1942 Mallinckrodt Chemical Works in downtown St. Louis was chosen as the site where the uranium used in the Hiroshima atomic bomb and other weapons would be enriched. That uranium, mined in the Belgian Congo, was deemed to be the purest on Earth, an average of 65% uranium oxide compared with American or Canadian uranium, which contained less than 1%.

Albert Einstein himself, warned by a Hungarian physicist friend not to let the Nazis get access to it, implored both the Queen of Belgium and the United States government to work a deal, and so the Queen sent the U.S. 1,250 tons of uranium ore from the Shinkolobwe mine for $1.60 per pound, and as the war continued, further purchases occurred amounting to $200 million annually. On December 2, 1942, Enrico Fermi himself loaded Mallinckrodt-purified uranium into a reactor underneath the University of Chicago’s Amos Alonzo Stagg Field bleachers triggering both the first self-sustaining nuclear reaction and the onset of the Atomic Age. Hiroshima followed.

After WWII ended, the 47,000 tons of atomic waste from the Project was moved around for 25 years to various sites throughout the city of St. Louis and North St. Louis County, including locations downtown, near the airport, and residential neighborhoods such as Coldwater Creek, before finally being shipped in 1973 to the West Lake landfill in North St Louis County, close to runways of the St. Louis’ Lambert International Airport, and also next to other residential communities, such as Spanish Village.

West Lake Landfill sits on 200 acres of land and is part of a larger complex called Bridgeton-West Lake that is divided into three sections: one area containing the radiological areas, (called “North Quarry”), an empty chamber which has become a buffer zone, (called “the Neck”), and a second landfill area that does not have radiated material, but contains dangerous volatile organic compounds, (called “South Quarry” or “Bridgeton”). In 1990, West Lake Landfill was listed on the National Priorities List making it a Superfund site. (Only the most toxic and dangerous sites receive Superfund status.)

The waste’s ownership changed hands several times since its arrival at West Lake, and is now owned by Republic Services, the second largest waste disposal company in the state of Missouri, who purchased it from Allied Waste in 2008.

Sources allege that it was Republic’s overly aggressive pulling of methane at the site that triggered the fire. They contend that by pulling at higher than industry standards, oxygen was inadvertently introduced into the landfill, triggering an exothermic reaction, and now the fire smolders between 60 and 150 feet beneath the surface. According to estimates from the State of Missouri Department of Natural Resources, it has already breached the Neck and is headed toward the North Quarry at a rate of roughly 300 feet per year. Some sources place it at only 700 feet (233 yards) away from the North Quarry – almost the exact length of Bellerive’s par-3 16th hole. Others disagree. Even so, computing that rate of progression, and accounting for the heat signature the fire emits, it could reach the North Quarry between 12 and 18 months from now.

COLDWATER CREEK AND SPANISH VILLAGE

Around 2010, nearby homeowners, such as those in the Spanish Village complex, noticed a chemical stench fouling the air. Their CO2 and smoke detectors were also triggering with alarming regularity for unexplained reasons. They learned, to their horror, they were living next to one of the most toxic Superfund sites in America. The odor came from chemicals like benzene, methane, sulphur dioxide, and other volatile organic compounds, but the specter of the Manhattan Project waste was even more frightening.

“If it hadn’t been for the stench of the noxious gases emanating from the Bridgeton landfill, many people would not have been aware that Manhattan Project radioactive waste was dumped in close proximity on the same property,” explains Cammisa, who has been nominated for two Oscars, two Emmys, and won the Special Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival in the course of her career. It was her HBO film, Atomic Homefront, a 2018 Oscar nominee, that drew national attention to the problem. “Meanwhile people in these neighborhoods, like those who lived along Coldwater Creek, have fallen ill or died from of all sorts of cancers for decades – cancers linked to radiation exposure.”

Residential neighborhoods bisected by Coldwater Creek lie just four miles from where the waste was stored prior to its arrival at West Lake. When the creek flooded, it sent polluted water washing over the banks and meandering throughout the residential neighborhood. For years, residents of communities by its banks died or were stricken with cancers in high numbers. These people built their homes with concrete mixed with contaminated water. They used that same concrete to pave their roads, and build their schoolhouses. And during major floods, Thorium-contaminated water seeped into their basements.

Most tellingly, the Department of Veterans Affairs lists 21 specific cancers caused by radioactive ionization. One local high school had young alumni die or become sick with all 21 of those cancers.

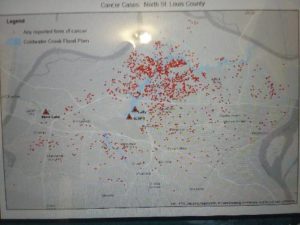

“If you look at maps of cancer deaths, they are heavily concentrated along the creek,” Cammisa notes poignantly.

Finally, after years of vacillating, this Tuesday, August 7, 2018, the federal government, via the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (a branch of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) confirmed that some residents who grew up in areas contaminated by radioactive waste decades ago may have increased risk for bone and lung cancers, among other types of the disease.

“BUT WHAT CAN WE DO? WE’RE JUST MOMS!”

Local residents were outraged and horrified. Just as Love Canal residents unified in the late 1970s to protest the storage of cancer causing toxins in their neighborhood and demanded the government buy back their homes, so too did local residents in St. Louis galvanize through Facebook groups, bulletin boards, and community meetings into “Just Moms STL.” Like Lois Gibbs, the “Accidental Environmentalist” who fought for the homeowners of Love Canal, ordinary moms and housewives like co-founders Dawn Chapman and Karen Nickel found themselves at the vanguard of a life-and-death battle with the EPA and the polluters.

“If you’re gonna meet, you have to call yourselves something. And we said, ‘But we’re just moms,’ and it stuck,” explained Nickel, a former Coldwater Creek resident diagnosed with lupus years ago. She had a hysterectomy at age 42 as well as lupus and fibromyalgia. Four of her children are seriously ill as well.

Even those few who knew about the radioactive waste at West Lake didn’t realize how dangerous it was until Just Moms started pushing back against the flawed data collected by the parties responsible for the dumping, data the Obama-era EPA relied upon to delay taking action.

“The EPA has always been involved, but more like a teen babysitting than a Federal Agency responsible for oversight of some of this nation’s most dangerous wastes,” cautioned Dawn Chapman. “Much of the data EPA has about our site was collected from the companies responsible for the waste. Sort of a nasty example of the fox guarding the hen house.”

It was only through their public battle with the EPA that more testing was done and the radioactive waste was found to be in more areas and closer to the fire. Poor Karen Nickel, for example, learned to her horror that she had followed the waste like some terrible will-o-the-wisp: first living near Coldwater Creek, then later moving to another site where the waste was later stored.

As their battles with Obama-era EPA officials continued, there were denials, delays, and ideas that never seemed to come to fruition – but no concrete action. For years, there was a genuine concern that a solution would not be found in time, even though the Army Corps of Engineers was working feverishly (as they had since 1997) to clean up the radioactive waste (with full suits and masks). In 2014 St. Louis County Operations released an Emergency Operations West Lake Landfill Shelter in Place/Evacuation Plan for St. Louis County and St. Charles County. Residents put together escape plans, grab bags, and first aid kits, ready to head out the door should the worst happen.

THE NEW ADMINISTRATION AND THE MEETING ON AUGUST 1, 2018

Happily, a change of administration has ushered in an era of responsibility, transparency, and problem solving. To the surprise and delight of not only Just Moms, but all affected residents in St. Louis, ideas and talk have turned into action and results.

“Since the new change in administration in 2017, the door has been opened wide for us to come in to the top of the EPA administration and share our concerns. It is hard to get an agency to admit they have made significant mistakes…especially when the people within are trying to protect their career and reputation. With some of the new folks at EPA, they don’t have to worry because those mistakes were made before them…so they have no problem acknowledging them. So I guess you could say not as much covering of their bottoms,” surmised Nickel. “There is also a clear push to get some of this waste removed from this site and an acknowledgement of the dangers this site poses for our community.”

The most palpable sense of the tide turning came just last week when Ann Wagner, the district’s U.S. Congresswoman showed up with State Representative for the region Mark Matthiesen in tow at a meeting between Just Moms and the EPA. The meeting could not have gone better for the residents: the politicians came in demanding answers and results, and new EPA Head of Superfund Task Force Stephen Cook was only too happy to give them.

Where once the meetings were contentious and disconcerting, suddenly there was only consensus and determination. When Wagner demanded a hard deadline for a determination on a final course of action, (declaring at one point, “we all at this table have PTSD from you guys jerking us around”), Cook firmly replied that September 30 of this year is the date when a final resolution will be announced. When Wagner bristled at the knowledge that Republic Services may have been trying to negotiate a more beneficial resolution for itself than the residents, Cook countered assertively that the September 30th plan will be implemented with or without Republic’s assistance – they’ll do the work or the EPA will get it done anyway and sue them for not complying – seemed to those at the meeting to be the tenor of the reply.

Best of all, without any prompting, the EPA also volunteered the information that they are going to be transparent and proactive in warning the communities about the risks the waste poses. Tuesday’s announcement by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry appears consistent with that declaration.

“Karen and I are even invited to Washington D.C. to meet with them on ways to improve the Superfund program,” said a grateful, hopeful Chapman.

As one veteran of the EPA of over 25 years candidly admitted to Chapman, with the old administration gone, “the chains are taken off. Now we can fix things with real answers,” not bureaucratic answers or result oriented decisions.

“Broken trust is being repaired,” Chapman stated.

BEYOND THIS WEEK’S PGA CHAMPIONSHIP

All of St. Louis County, including Bellerive Country Club, are within the affected area and under the Emergency Evacuation Plan and have been so since 2014. See https://www.stlouisco.com/Portals/8/docs/document%20library/police/oem/lepc/WestLake%20Plan%20-%20FULL.pdf According to that plan, “If the “sub-surface smoldering event” reaches the radiological area, there is a potential for radioactive fallout to be released in the smoke plume and spread throughout the region.”

How much radiation is in the air and around the landfill? Good question. No one knows for sure, but according to a report from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission –

(osti.gov/scitech/servlets/purl/7016008

<http://www.osti.gov/scitech/servlets/purl/7016008>) an analysis of

surface soil contaminants showed daughter products of both

U-238 and U-235, including Ra-226, and Th-230.

As Bellerive is eight miles away and, fortunately, the fire has not yet breached the North Quarry, players and spectators were safe for this week. Nevertheless, it was not an unreasonable question to ask the PGA of America how much research went into assuring that Bridgeton-Westlake would be safe in August of 2018, and whose research was relied upon to make that decision? It’s also reasonable to ask why a charitable contribution cannot be made to these homeowners.

One can also understand the PGA of America’s reticence to discuss the issue. No matter what answer they give, it opens the door to criticism from some end. It also raises the question of what other golf courses might be in close proximity to Superfund sites, and how safe are those courses.

Golf should actually be a shining example of how the private sector has been remarkably successful in reclaiming toxic properties, and how our sport is at the forefront of environmental responsibility and problem solving. Say what you like about Donald Trump as a person, but he finished Ferry Point in two years where the City of New York couldn’t do it in 15, and one of the most viscid landfills in New York is now a course so pristine, it holds PGA tournaments. Many other courses throughout the golf world, both private and public have achieved similar successes.

“Some of the underlying materials at the Bayonne Golf Club – like other sites on the Jersey shore of the New York harbor – contained petroleum, as well as municipal landfill material, and oil that had spilled from its storage,” explains Eric Bergstol, owner and designer of Bayonne, regarded by many as arguably the greatest engineering achievement in modern golf history. He converted desolate wasteland and unsightly landfill into a golfing Shangri-La, one of the world’s top courses. “We built a slurry wall that keeps everything on the site inside the site. We also built a leachate collection system, a methane collection system, and we capped the entire property – all 135 acres – and made it impervious to water: no water can enter or exit the site.”

At Bayonne, where they purify no less than 60,000 gallons of water a day, they did this all without any public money. The private sector is more than capable of doing significant cleanups, though there has to be a mechanism to it – there was an end product at Bayonne and a process that was efficient.

The same happened at Fossil Trace Golf Club in Golden, Colorado. Another 135 acre parcel of property transferred from private hands to the City of Golden. The property not only contained hazardous fly ash from an old ceramic plant, storm water retention areas were needed to protect Golden from flood from run-off, and lowland pond areas posed different drainage issues, there were also 64 million-year old dinosaur fossils found on the site. As Your Author wrote in an earlier piece for Golf Course Trades magazine:

“When environmentalists and scientists heard that the land where the archaeological treasures were located was being transferred from private to public hands, they united into a powerful bloc determined to protect the fossils. And when they heard it was a golf course that was proposed, you’d have thought every banshee in Ireland had descended upon eastern Colorado, shrieking all the cacophony of Hell.”

But golf architect Jim Engh, never one to shy away form a complicated project, united with the Army Corps of Engineers, to put together a plan where he preserved the fossils, cleaned up the fly ash safely, and protected the wetlands. He even enlisted the environmentalists to help protect and preserve the fossils, turning political enemies into ardent supporters. Together, science and golf showed the world the state-of-the-art in both crafts as unlikely, but successful bedfellows.

While golf is throwing one of its biggest parties of the year, just eight miles away, families are fighting the toxic nightmare next door. As Golf World’s Ron Sirak once sagely opined, golf and golfers can save lives. The same selfless, altruistic ethos that goes into calling penalties on yourself, can be channeled into charitable works for worthy causes. There’s plenty that golf can do for St. Louis – a city with rich golf heritage, from Lew Worsham winning the U.S. Open in 1947 at St. Louis Country Club, to Nick Price and Gary Player winning PGA Championships, to the many great golf courses designed by quintessential architects throughout American golf history. In this case, we really don’t to look far to find it. These are average, everyday Americans like you or I. Up against the government, huge corporations, and dangerous radiation, they can use all the help we can muster.

QUESTIONS WE ASKED THE PGA OF AMERICA:

How and when did you find out about it [the landfill fire and the existence of the waste]?

What is your exact understanding of how dangerous/volatile this situation is?

Whose facts and information did the PGA rely on to make a determination as to how safe it is – the EPA, the Army Corps of Engineers, the State of Missouri or Republic Services?

Was there any discussion of whether Bellerive should swap places with a future PGA Championship site as a safety measure?

Is there any plan on paper to handle what happens if between now and the tournament something happens at Westlake landfill?

In the 70s, the residents of Love Canal had their homes bought back by the government. Was any consideration given to making a charitable contribution to the victims/homeowners and their families?

The response we received from PGA of America President and CEO Peter Bevacqua through Communications Director Julius Mason was as follows:

“Because this is not related to the PGA Championship we would not have any comment on this subject.”

We also reached out to Russ Knocke, Vice President Public Affairs Republic Services, but have not heard back from him as of yet.